I can only imagine the grief that people had to endure having witnessed the famous climax to The Godfather Part 2 in 1974 and having to wait sixteen years for the next instalment. The ending to Part 2 is remembered with such fondness because it manages to conclude several of its intertwining plot-lines within one heavily dramatic five-minute sequence, and although this chapter is now concluded, you know that nothing will ever be the same again. A whole new plethora of stories has just risen from the ashes of a vicious and heart-wrenching conclusion. The sense of despair and defeated pride that has encompassed the saga until now is intensified to its magnitude. As Michael Corleone orders for the deaths of multiple men, one of which being his own brother, a brooding, nightmarish piece of music haunts the unfolding events, exemplifying the horrors of death that come hand in hand with all the suave and luxury that comes with being a gangster. It’s this piece of music, swelling with uncertainty, that reprises in Part 3, cementing itself and the dreadful reason it came to exist as a thematic cornerstone in the life of Michael Corleone.

Films I reference/potentially spoil in this article:

- The Godfather (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1972)

- The Godfather Part 2 (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

- The Godfather Part 3 (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1990)

- Apocalypse Now (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

- The Irishman (dir. Martin Scorsese, 2019)

I found The Godfather Part 3 to be the most accessible of the trilogy in terms of you being able to relate to its characters on levels of empathy and decision-making. The first two are fuelled more by the attention to detail in the strategy and tactics that allow their criminal organisations to operate. These films are masterclasses in depicting action causing reaction, mapping out this grand chess game where pawns are replaced with low-level mobsters, knights with dangerous family members and kings with the Dons whose worlds revolve around them. The films rely on their masterful screenplays and character writing to allow the audience to associate with them, but, unlike in other Coppola films such as Apocalypse Now, the direction isn’t going to dictate to us how we should feel about any particular character. Each element of the filmmaking craft is articulated in such a way that Coppola and writer Mario Puzo never tell you how to feel about something that has happened. This is what makes the films so singular and engaging in conversation; the actions of the characters, whether great or terrible, are depicted in a similar and neutral fashion, hence blurring the lines between right and wrong for each individual viewer. The power that this uncertain swinging of the moral pendulum creates makes the trilogy fun to dissect. Part 3 however, changes things slightly, putting a little more focus on these emotional cues, which is done by applying a turbulent and relentless pressure on the Don of the ever-hectic Corleone family.

Part 3 focuses on Michael’s inevitable spiritual descent, opening similarly to Part 1, which is with a massive family party. The difference this time is that Michael is the old and frail one. He bumbles around the room, still with an ominous and weighty presence, but his being is far less threatening and serious. At this event, however, which is celebrating an honour he received in the opening sequence from the Pope, Michael’s focused attention is unshakingly placedupon his family, primarily on his ex-partner Kay and his two children, Anthony and Mary. The former two, Kay and Anthony have become estranged. Michael lacks the power to command his son to persevere and finish a degree in business, as he is committed to dropping out and pursuing a career on stage. Kay tells Michael regarding failing to come to an agreement with his son, that he only has himself to blame as Anthony certainly inherited his stern “no” from him and not her. Witnessing Michael’s attempts to fix this ever-increasing parting of ways between himself and his family is a powerful way to depict his descent from the top; even his son doesn’t want to be part of the infamous, back-stabbing Corleone Mafia history. It is immediately present that Michael is not the gangster he once was, and nor does he want to be; only now is he trying to retain the closeness his family is rapidly losing. He seems to be a little too late though and too far past redemption, the death of his brother Fredo still haunting him, unforgotten. However, such old habits die hard; in fact, these “old habits” are intrinsic to Michael’s nature, so to merely shake off his criminal history and to cleanse his soul and mind is a lot easier said than done. To his credit though, he does try; it’s his nephew Vincent Mancini and family “friend” Joey Zasa that create obstacles for him en-route to his quiet departure.

Image Credit: Alternate Ending

A central theme of the film that is also present in Part 2is reflection. At the end of Part 2, moments after killing his brother, Michael reminisces on a scene from earlier in the saga, recalling a time of him and his brothers together at a family meal. The scene concludes with him alone at the dinner table, a visual metaphor that is carried through Part 3; Michael is estranged and vacant, present in each scene yet disconnected from everyone. He’s tired, and when we see him counselling the Mancini and Zasa feud, we can tell just how done he is with it all. Through this feud that ensues throughout Part 3, Michael is reflective of his past, observing a life of futile battle where there are no winners, and if they are winners, for what, money, respect? The realisation that these conflicts reward their participants with intangible prizes makes Michael willingly closer to that next step in stepping down, reuniting with Kay and retiring to their massively romanticised and treasured, utopian Sicily. Yet again, however, these old habits die hard and Michael cannot blame the actions of others for his undying addiction to maintaining the holy-like title as Don of the Corleone family, still working tirelessly to shield them from the speculation of the investigative press.

The Godfather Part 3 comes with everything the first two delivered, and in many cases, I enjoyed it even more than its predecessors. It’s a grand spectacle of cinematic beauty where the craft is mastered by all those that partook (perhaps other than Sofia Coppola’s performance which is somewhat deserving of all the negativity it received; to her credit, however, her performance isn’t truly awful, but place any non-professional actor in one-on-one scenes with Al Pacino and Andy Garcia and cracks will not only begin to show but become distracting). It’s a wonderful conclusion that tracks the demise and last few decades of yet another Don generation of the Corleone family tree. Calculated methods of violence and precise strikes between rivals and rogue gangs are still present but many acts of rage are replaced with a Don at his demise, contemplating the acts of violence that surround him and mirror his own history. Starkly contrasting imagery of Michael aids in displaying this downfall. Michael now has new battles such as his health. Regardless of his status, one scene in a churchyard sees Michael trembling and pleading for a candy bar due to his diabetes. Shortly after this, we watch him confess to a priest about his brother Fredo, begging for repentance. It’s a masterful utilisation of juxtaposition, masterful because it introduces a lesser-seen side to a character who we’ve known as stern and violent, now emotional and vulnerable.

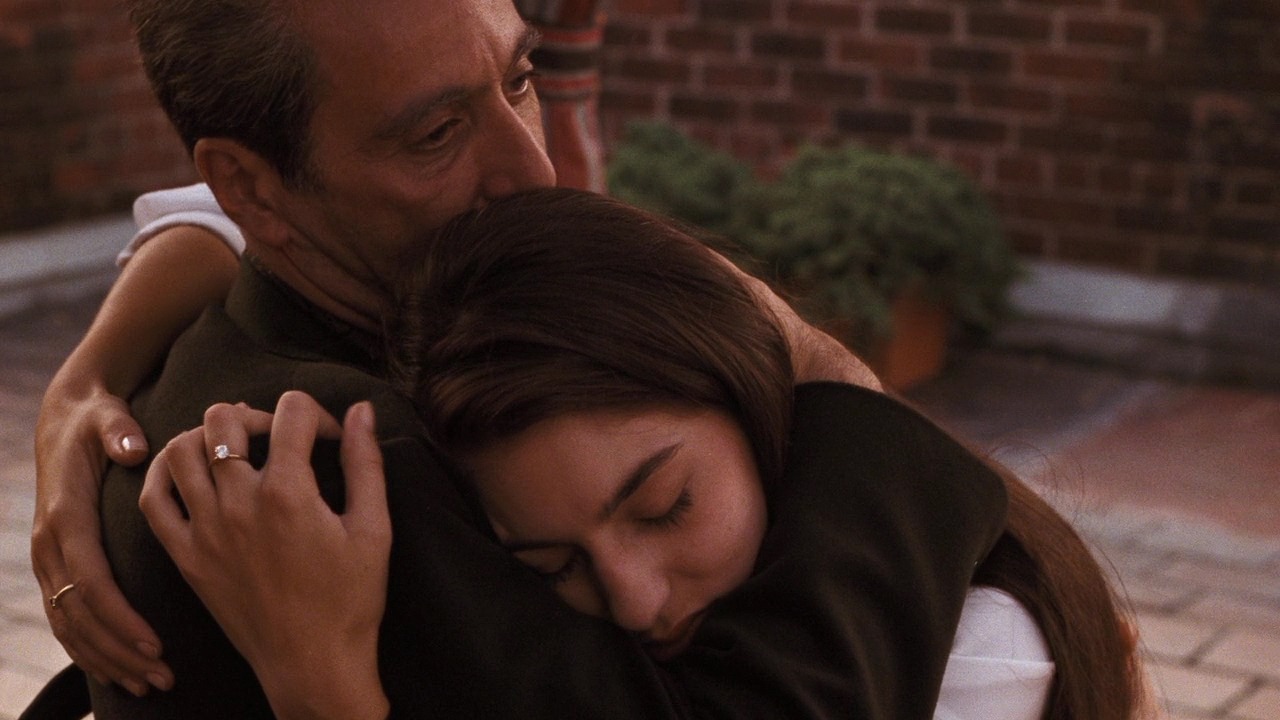

It’s scenes like these aforementioned why I didn’t need to consult the internet for the Corleone family tree every now and then. Characters in Part 3 are now characterised by their emotional arcs and ambitions of a more sympathetically relatable nature rather than their actions, attacks and outbursts to clamber to the most powerful position possible. Although I much preferred Part 3, the film is comparable to Scorsese’s latest, The Irishman, where similarly, I only felt a rawer sense of emotion for its protagonist near the end when the lead character is presented with issues out of his control, primarily old age. Both remarkably achieve this in their ending sequences. Michael Corleone’s death is almost as bittersweet as it is darkly comic and depressing. The death of his daughter Mary sees Michael reminisce dancing with her, then his first wife Apollonia, and then Kay, two of which have been killed by his lifestyle, the latter now undoubtedly resenting him. Then, we see a much older and frailer Michael, finally resided in Sicily, but alone. Sitting on a chair in the dusty courtyard, he topples onto the ground and the credits roll. It’s a wonderful conclusion in the way that it cements and reiterates everything that we were warned of from the start. Michael isin fact too late to repent and plead forgiveness.

This is the most morally mature entry to the Godfather trilogy. Where it may lack in the intense, mob-driven drama of the first two, Part 3 exceeds in its abilities to reflect and create a fulfilling conclusion. It manages to bring back to Earth the driving elements of the ruthless climb to mob-fame in a form that makes us recognise how nobody is ever truly safe, albeit from our peers or ourselves.

Loved:

- An impressive and bold conclusion to a trilogy that had many potential stories to follow up on

- Filled with incredible performances

- As dramatic and entertaining as the first two instalments

Didn’t Love so much:

- Occasional lulls in pacing, as with Part 1

- Reprisals from more characters from parts 1 and 2 would have been welcome